Why Maths Lesson Fail and How to Make Success Inevitable

Webinar Snapshot by Martin Ravindran

In his webinar Why Maths Lesson Fail and How to Make Success Inevitable, Brendan Lee begins by calling to mind the struggles that many of us have felt in classrooms. Namely, the fact that teaching is complex, and that a teacher has to balance behaviour management, pedagogical choices, and contingent decision making while standing in front of a (sometimes less than captive…) audience. It is not surprising then that we sometimes walk away feeling like a lesson did not have the intended impact. So how can we, as educators, optimise instruction and walk out feeling proud and confident of the fact that our students have learnt something?

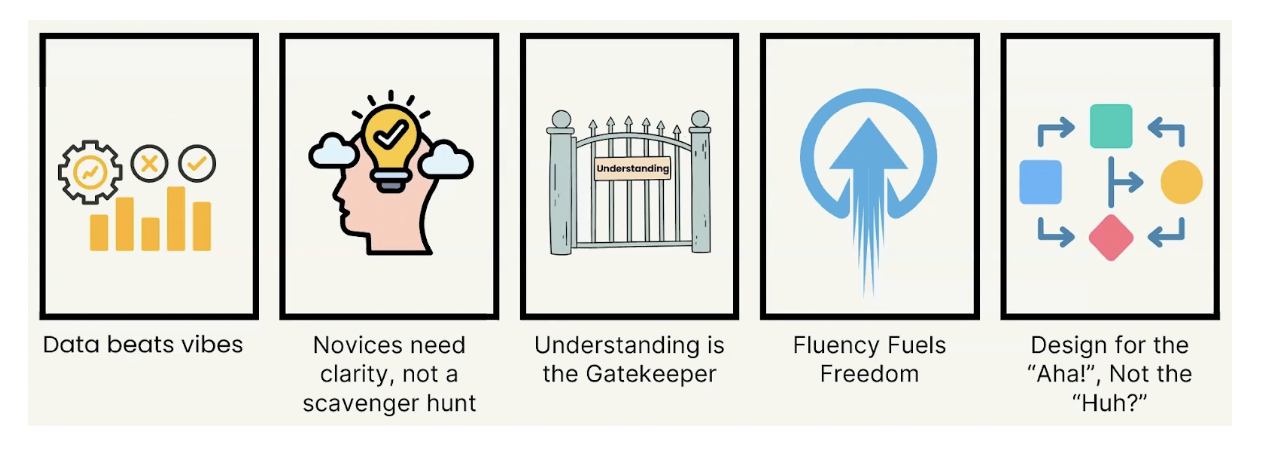

With reference to the Instructional Hierarchy, Brendan’s main message is that learning happens when there is an alignment between instruction and a learner’s stage of learning. To this end, he proposes that there are 5 levers or big ideas that can help provide the conditions for effective instruction.

Data beats vibes

Professional judgement and teacher expertise/experience are important. Ultimately however, what needs to fuel these professional judgments should be data. This is where assessments, summative and formative alike, play a central role in helping us determine which stage of learning our students are at. In-class performance is desirable, but can be a poor proxy for learning, and until we can properly assess where learners are at, we cannot plan for the next step.

Clarity, not a scavenger hunt

For our novice learners in particular, clarity of instruction and clarity of concepts is key. Novices are still in the acquisition phase of learning, and extraneous or unnecessary activities that take mental resources away from the learning come at the expense of learning. To create clarity, lessons require a clear end goal, and students should be guided to this end goal with scaffolding that fades over time as they grow in their proficiency.

Understanding is the gatekeeper

A “busy” classroom is not necessarily a reflection of the amount of learning happening in the classroom. Engagement with an activity should not be confused with engagement with the learning. Sitting behind this idea is that checks for understanding, and not just listening, should be routine within lessons to ensure that students are focusing their attention on the content at hand.

Fluency fuels freedoms

As Brendan puts it, attempting to learn new Maths without fluency is akin to “climbing a mountain with a bag of bricks”. Fluency is not the end-all and be-all, and educators all want our students to attempt challenging and novel tasks. However, fluency is a foundational block that allows students to dedicate their thinking to the new content. To build this fluency, small repeated doses of timed practice after something has been taught can not only be helpful for learning, but motivating as well when students track their progress over time.

Design for the “Aha!”, not the “Huh?”

Last but not least, Brendan comes back to the idea that if we want students to have that “Aha!” moment in learning, it is less about having them wade through problems that they have not been taught to solve, and more about designing a step-by-step sequence of learning that ensures students have the prerequisite understandings and necessary fluency to tackle complex tasks. This idea encapsulates the previous ones, and highlights the need for a well sequenced progression that our learners can work through, with sufficient reviews and checks to ensure that knowledge is retained. When the building blocks are solid, students will then be equipped to make conceptual and curricular leaps, and reap the rewards of their prior learning.

In summary, Brendan reminds us that effective instruction is data-informed (both from the research and from our students) and sequenced in ways that align with our learners’ current stage of learning. Clear and specific delivery of content, followed by a healthy dose of checks for understanding and fluency practice, set our learners up to grasp increasingly complex ideas and material

DEVELOPING A KNOWLEDGE-RICH SUBJECT CURRICULUM

Heather Fearn

(Webinar featuring: Heather Fearn - Snapshot blogpost by Samantha Charlton)

Heather Fearn’s webinar, Developing a Knowledge-Rich Subject Curriculum outlined some of the key ideas that schools and teachers should consider and understand when enacting a knowledge-rich approach to curriculum.

Some of Heather’s focus areas included:

The significance of subject-specific knowledge in developing students’ broad and interconnected schema of knowledge. T

The ability to think like an expert; whether a chemist, literature expert, philosopher, geographer or artist, depends on a substantial body of disciplinary knowledge built over time. To make this possible, we need to untangle our previous integrated-studies approach in areas such as History, Geography, The Arts and Science so each subject can be taught cumulatively and coherently.

The difference between hierarchical and cumulative knowledge. Hierarchical knowledge develops in a necessary order because each idea builds upon the one before it. Maths is an obvious and familiar example of this. Cumulative knowledge, by contrast, grows over time as securely sequenced concepts are revisited, deepened and connected within and across subjects.

The challenges of teaching coherently without a school-wide approach.

Individual teachers cannot easily deliver well-sequenced, cumulative instruction without shared structures. A clearly mapped, carefully planned scope and sequence across subjects ensures that students encounter the right content at the right time, and that teachers avoid both unintentional gaps and unnecessary repetition in what students learn.

This level of interconnected knowledge and understanding begins with carefully chosen and taught building blocks.

Heather’s points about the vagueness and lack of clarity in the curriculum resonated with me. She showed how unclear expectations make coherence difficult and often lead teachers to plan in inefficient and unsustainable ways. While adhering to a specific and granular school-wide scope and sequence, or the use of well-designed resources that were not developed in-house, can initially feel as though they reduce a teacher’s autonomy or limit opportunities for creativity, the wider impact is clear: students are able to build more secure and substantial knowledge. An added benefit is that teachers can use their planning time more effectively, focusing on how they will teach rather than trying to decipher what they need to teach.

Heather’s webinar reinforces that clarity, coherence and disciplinary knowledge matter. As many schools shift their practices within other aspects of teaching and learning, the development of a knowledge-rich curriculum that provides clarity for teachers and secure learning for students becomes a valuable asset. It strengthens students’ knowledge and builds the critical thinking and confidence that effective learning depends on.